“What is the use of democracy if hungry children cry?”

"We have a unique situation where it is not the people who create the state, but the state must create the people," Sakrat Janovič, a Belarusian writer from Białystok (Poland), noted aphoristically in 1992. These words sounded dissonant: it seemed that Belarus’ rule by the former Soviet nomenklatura was coming to an end and a nationally oriented elite was about to come to power.

However, it was Aliaksandr Lukashenka who won the presidential elections in Belarus in 1994 under the slogans of restoring the economic ties destroyed as a result of the collapse of the USSR, restoring the status of the Russian language as a state language, and promising the integration of the newly independent Belarusian state with its former metropole, Russia.

Belarusian writer Vasil Bykaŭ in his memoirs "The Long Road Home" noted that by concentrating on the promises to resuscitate the economy, fight poverty and corruption to the voters, Lukashenka hit the mark:

"The people went after the tough, forceful, pragmatic director of the collective farm, whose ideas were simple and fully understood. He rushed to Russia to extract bread, gasoline, gas, without which it was not only impossible to [nationally] "revive," but also to survive the winter. Of course, many understood and felt that this deprives Belarus of sovereignty and pushes it away from democracy. But what good is democracy if hungry children are crying?"

"A widely known myth, still perpetuated by Lukashenka himself and state media, is that he was the only deputy of the Supreme Council of Belarus who voted against the Belavezha Accords*," writes Belarusian political scientist Valery Karbalevich in his book "Aliaksandr Lukashenka: Political Portrait." In reality, Lukashenka abstained from voting, as recorded in the meeting's protocol. Nevertheless, it was Lukashenka himself who, after taking the presidency, monopolized the discourse on the integration of Belarus and Russia.

Pro-Russian political forces in 1994 made a bet on Lukashenka. In the early period of Lukashenka's rule, individuals with pro-Russian views displaced those who were more Belarusian-centered from state-owned television, radio, and print media at both national and local levels. The pro-Russian orientation of the regime did not contradict the expectations of the majority of the Belarusian society, many of whom had relatives, studied, or worked at different times in the USSR or the Russian Federation.

At the same time, the creation of a confederative or federative state based on existing independent Belarus and Russia faces not just legal and patriotic obstacles, but also a fundamental mismatch of interests. Russia is a clear case of a resource-based economy. If during the time of Peter the Great, this country was selling hemp and wood, now it sells oil, gas, and timber. Belarus, on the other hand, has a resource-intensive economy: it does not sell but buys resources, and it is important for Belarus to sell industrial goods. These differing interests drive cooperation rather than merger, and the priority is good friendship and trade. However, as always, there is a conflict between buyers and sellers. Aliaksandr Lukashenka has acknowledged this, saying, "A new generation has arisen, and the old one has realized that we can live and cooperate in a completely different way, like close relatives. Today, Belarusians want to be with Russia, but live in their own apartment."

However, Vladimir Putin has a different view, which fits more into the concept of a divided people who see themselves as a united community but live in different countries and strive to unite in a single state. "The Russian and Belarusian people are, in my opinion, the same as the Ukrainian and Russian people. They are almost the same in the ethnic sense of the word and from the point of view of our history and spiritual roots. That is why I am very happy about the rapprochement between us and Belarus," Putin said on December 19, 2019.

In the suffocating embrace of the metropole: hooked on the price needle of Russian oil

Dzmitry Kruk, a senior research fellow at the Belarusian Economic Research and Outreach Center (BEROC), in an interview with Media IQ, explained why the dependence of the Belarusian economy on Russia is not predetermined.

Kruk believes that the current dependence of Belarus's economy on Russia is not an inevitable outcome. Rather, it is the result of a lack of willingness to prioritize future goals over present considerations at a specific point in time. Additionally, it reflects the political decision to pursue closer ties with Russia.

According to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Belarus, Russia is the main trading partner of Belarus, accounting for 49% of the value of total goods trade in 2021, 41% of exports, and 57% of imports. In 2022, according to data from the first half of the year, Russia's share of Belarusian trade increased to 58%. The authors of the Belarus Change Tracker analytical report note that this was due to both a reduction in turnover with EU countries and an increase in trade with Russia: during the first half of the year, exports to Russia increased by 23%, while imports from there increased by 4.4%. Thanks to the growth of exports to Russia, Belarus recorded a positive trade balance for the first half of 2022. According to the Federal Customs Service of Russia cited by TASS agency, Belarus accounts for 4.9% of Russia's total foreign trade turnover.

Belarus supplies Russia with food products and agricultural raw materials, vehicles, machines, and equipment. The main components of Russian exports are gas, oil and petroleum products, machines, means of transportation as well as non-precious metals.

Dzmitry Kruk notes that "the lion's share, over 50% of Belarusian exports, goes to the Russian market, and if we talk about the last year, especially after the sanctions, after the start of the war, then this share is only increasing."

According to him, throughout the past 30 years, preferential prices for oil and gas have been a very important factor for both the dynamics and the development of the Belarusian economy. "The recent history with the sale of a significant portion of tax sovereignty in exchange for compensation of Russia's tax maneuver (simultaneous decrease in export customs duties on oil and increase in tax on extraction of minerals in Russia, leading to an increase in oil prices for Belarus and insufficient export customs duties for the Belarusian budget. - Note: Media IQ) shows that [Belarusian authorities] are so tightly hooked on the price needle for Russian oil that adaptation to market prices causes a reaction when the profitability of oil refining goes negative," says Kruk. In such a manner, by this logic in order for the economy to feel good, it must sacrifice all of its future prospects in order to maintain the viability of oil refining. According to him, this situation indicates that the Belarusian economy is hooked on Russia's oil needle.

"If we subsidize the entire Belarusian economy, it means that we, Russia, are subsidizing the entire gas supply for the country. This issue, you see, is very strange - Russia should subsidize another country in the same way as the most subsidized region in Russia. It's odd," said Putin on December 19, 2019, linking price preferences within the Union State with the deepening of the integration of Belarus and the creation of supranational bodies.

The official stance of the Belarusian government is that cooperation with Russia is mutually beneficial and based on loan provisions, rather than subsidies.

However, Media IQ's 2019 study found that the Belarusian media, including state-owned outlets, do not commonly portray this narrative. Non-state media also rarely mention this narrative. Instead, they frequently state that in the past, Russia subsidized Belarus and will continue to do so only if the two countries deepen their integration, establish supranational organizations, and if Belarus abandons its national currency.

Kruk states that if Belarus faced a shortage of financial resources or difficulties in the economy, "the first thought that came to mind for Belarusian officials was to ask for money from Russia."

According to RBC, from 2008 to 2020, the Russian government and VEB.RF, Russian state development corporation, provided Belarus with at least eight loans. As of the end of Q1 2020, Russian loans accounted for about 48% of Belarus' external government debt, or $7.92 billion.

On December 21, 2020, the Russian government approved a project agreement to provide Belarus with a loan in 2020-2021 of $1 billion in two tranches of $500 million each in 2020 and 2021. The first tranche was received on December 30, 2020, and the second on June 2, 2021.

On November 16, 2022, an intergovernmental agreement was signed for Russia to provide a loan to Belarus for the amount of 105 billion Russian rubles for import-substituting projects.

"Today, the lion's share of Belarus' debt is either directly to Russia or to the Eurasian Development Bank, which is a structure within the EAEU (Eurasian Economic Union) and largely exists on Russian funds, so I wouldn't separate them. And a significant portion of external debt is also related to Russian banks," explained Kruk. According to him, the restructuring of the Russian debt and payments for the years 2022-2023 played an important stabilizing role for the Belarusian economy. However, at the same time, "by pulling this thread of financial dependence, Russia can also influence current issues," he notes.

War Threatens to Devastate Belarusian Sovereignty: Will it be the End?

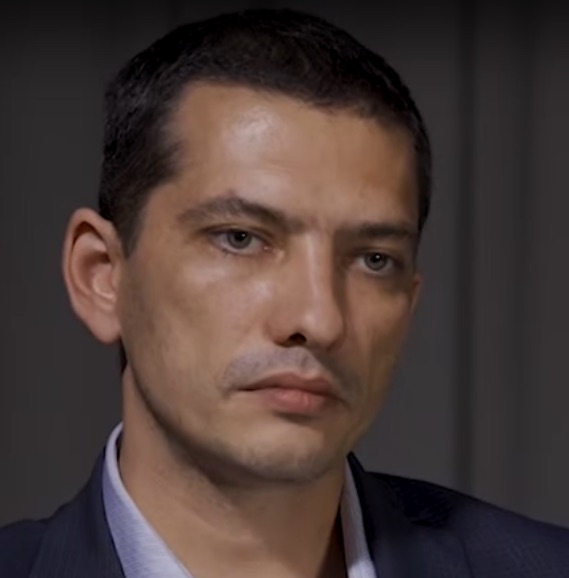

The war in Ukraine is the driving force of the political processes in Belarus, according to Artyom Shraibman, founder of Sense Analytics and political analyst. In a Media IQ interview, Shraibman discussed the validity of the claim that Belarus is occupied by Russia.

"In a legal sense, Belarus is not considered an occupied country because its civilian administration has not been replaced by a military occupational administration from Russia. It's evident that Belarus has lost a portion of its military sovereignty and cannot control the actions of Russian military on its territory or in its airspace. However, this doesn't qualify as occupation," says Shraibman.

He suggests that this resembles the system of satellite states that past empires had: "The Soviet Union had satellite states in Eastern Europe, which also hosted Soviet troops and allowed these Soviet troops to pass through when they went, for example, to suppress the uprising in Czechoslovakia. Hitler's Germany had its own satellites, which even participated in wars, in the [Second World – Media IQ] war on Hitler's side, but we still do not consider them to be countries occupied by Hitler's troops."

According to Shraibman, the concept of an "occupied Belarus" is appealing because it allows distinguishing responsibility between the Belarusian people, who do not support the war, and their authorities who do not represent them and lost the 2020 elections. "And that's why I understand why politicians make such statements," he admits.

He doesn't believe that Belarus has burned bridges with the West. "The same satellites of the Soviet Union became independent, fully sovereign countries, established normal relations with the West, they even became the West after the Soviet Union disintegrated," says Shraibman. At the same time, he believes that returning to the path of normalizing relations with the West will only be possible after a serious weakening of Russia - so that it loses the ability to control its satellites. The expert doesn't see any entity within Belarus that could take control and steer the country away from the heavy control and suppression by the Kremlin.

During the press conference on December 2, 2022 in Warsaw, Pavel Latushka, a representative of the United Transition Cabinet established by Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, explained the purpose of declaring Belarus as occupied territory. "Recognition of the status of occupied territory in Belarus gives us the opportunity to legally de-facto and de-jure recognize alternative power organs. This gives us the opportunity to create the Armed Forces of the Republic of Belarus outside its borders. It gives us the right to create a national liberation movement within Belarus. And all these actions will be legal. We are raising the issue of de-occupation.”

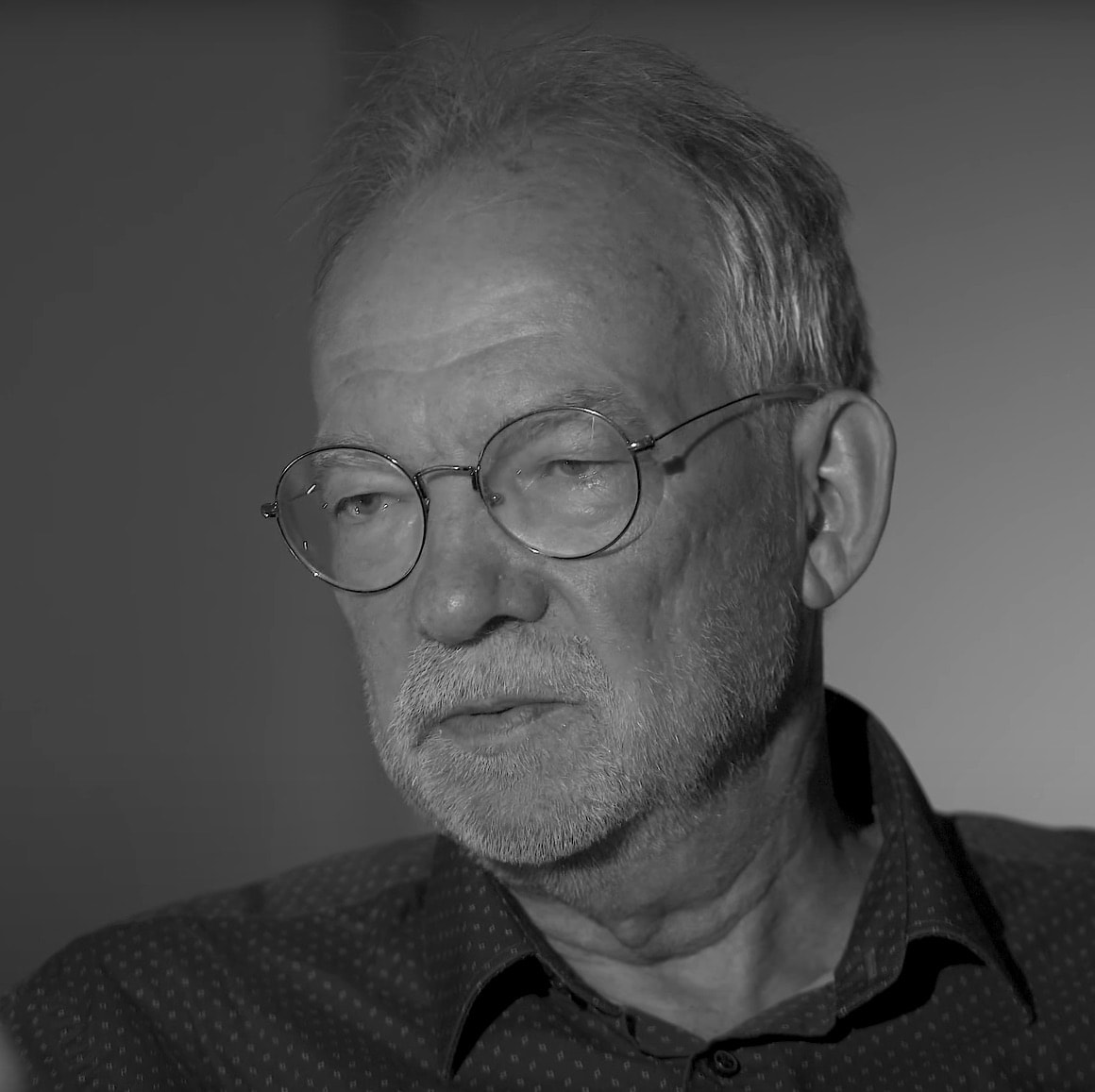

What do Belarusians actually think about the war in Ukraine? In an interview with Media IQ, Andrei Vardomatsky, Director of Science at the Belarusian Analytical Workshop (BAW), explains how the war in Ukraine is being perceived within Belarus and to what extent Russian perspectives on the war are influencing the thoughts of Belarusians.

Vardomatsky reports that the results of polls taken among Belarusians show that they have a neutral and sovereign orientation, rather than a dominant orientation towards the East or the West. He notes that over the past few years, there has been a decline of 10-15 percentage points in the number of people who would prefer an alliance with Russia when asked the question, "Would you prefer an alliance with Russia or with European countries?"

Vardomatsky says that for Belarusians, their relationship with Russia is a deeply held value and that albeit such values change slowly, they still do with time. Vardomatsky talked about a study conducted in 2019 which showed that the positive attitude of Belarusian respondents towards Russia was not so much based on Russia being one of the main trading and economic partners, but rather on non-economic reasons: common Slavic values.

According to a study conducted by Vardomatsky on March 16-26, 2022, two-thirds of surveyed Belarusians opposed the use of Belarus' military infrastructure to support Russia's aggression in Ukraine. "In regards to the potential deployment of Belarusian troops to participate in the war in Ukraine, the dominant attitude among Belarusians is negative. Only 11 percent, or one in ten Belarusians, responded positively to this idea," says Andrei Vardomatsky.

Belarusians are divided in their assessments of who is to blame for the war in Ukraine: 24% blame Russia, 20% blame the United States, and 17% blame Ukraine. Vardomatsky explains these results as an "echo of the Russian world" that is present in media narratives.

In an interview with Media IQ, political scientist Volha Kharlamava formulated the task for Belarusian patriots as breaking away from Russia.

"I believe that the Russian language is a means of influence, a means of shaping imperial and post-imperial consciousness. Russia uses the developments of the Soviet Union and modern developments in order to keep countries dependent or under its influence very effectively and efficiently," she stated.

Kharlamava suggests that Russian media hold more sway over Belarusians than their Belarusian counterparts, whether state-controlled or independent. "This is a post-imperial idea that one's own cannot be as high-quality or as convincing as the Russian one," Kharlamava believes.

She claims that the Belarusian state media imitates the Russian media by promoting identical narratives, formulations, and theses. According to Kharlamava, this is the consequence of the decades of information and psychological operations carried out by Moscow that adversely affected the consciousness of Belarusians.

Historical Lessons: "Independent Belarus is an Existential Threat to the Old Muscovite State"

The foundation for the current situation regarding Belarusian national identity and Belarusian-Russian relations was laid years and even millennia ago, according to historian Cimafiej Akudovič in an interview with Media IQ.

Akudovič notes that it is necessary to begin counting from the moment when the proto-state formation of Rus’ was broken into several large parts by the Mongol invasion. "Several such alliances were formed, each of which is a piece of Ancient Rus'," he explains. The historian mentions the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia (also known as the Kingdom of Rus’), the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Ruthenia and Samogitia (located in modern-day Belarus, Lithuania, and Ukraine), the Novgorod Republic, and the Rostov-Suzdal Principality, which later became Muscovy.

According to Akudovič, two centers emerged: The Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Grand Duchy of Moscow, both of which claimed the heritage of Rus'. "Everything revolved around Rus’, the heritage of Kyiv, the heritage of Byzantium, the heritage of Orthodoxy. This struggle ended with a great victory for Moscow and, to put it simply, a terrible turning point that occurred at the end of the 18th century, when Russia, together with Austria and Prussia, divided the Commonwealth – Russia took the entire territory of Belarus for itself," he explains.

As a result, official Russianness came to the Belarusian lands, although it was not present before. Meanwhile, the "tutejšyja" (local) culture of Old Rus’, Belarus, which had a strong Polish influence mixed with Catholicism, was completely trampled and destroyed, despite its own Orthodox and Uniate traditions.

"A completely different Rus' came to our lands, a completely different civilization that called itself our own. 'We have freed you, we have come, we have returned!' although it was a deception. It's a completely different culture. And all our further problems are probably connected with this deception," believes Akudovič.

The historian highlights that for the next two centuries, the Belarusian lands had restrictions on the development of their local culture and national self-awareness. He draws parallels and distinctions with the situation in Ukraine, where comparable cultural struggles took place. Akudovič explains that the Zaporizhzhya Sich, which fought against "not their type of Ruś," was the core of the Ukrainian resistance, whereas the Belarusians tended to be more open to combinations and compromises.

"For Moscow, Ukraine is a threat, not because a nuclear missile can arrive three seconds faster from there than from the Baltics, but because it represents a different, more correct Rus’. That's why Putin started the war – for him, it's an existential threat to his imperial Russia," says Akudovič.

According to Akudovič, Putin sees Belarus as it is imagined by most Belarusian of the Belarusian society as a threat. However, Putin doesn't really understand or acknowledge the existence of Belarus beyond Lukashenka and some groups he perceives as similar to Ukrainian Banderites, who are not seen as threatening as the actual Banderites. Therefore, Putin trusts Lukashenka more and doesn't give much thought to Belarus, especially now that Ukraine is a bigger concern. However, in the grand scheme of things, an independent Belarus is also seen by him as an existential threat to the Russian Empire.

During the time when Belarusian lands became part of the Russian Empire after the partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Orthodox Church played a significant role in the Russification of the annexed territories.

The phrase "What the Russian bayonet did not accomplish, the Russian official, Russian school, and Russian priest will" is commonly attributed to Mikhail Muravyov, the Governor-General of the Northwestern Territory.

During the Soviet era, Count Muravyov was portrayed in Belarusian textbooks as a brutal suppressor of the 1863-1864 liberation uprising, earning him nicknames like "gallowsman" and "cannibal". Under his rule, Belarusian Orthodox churches were also given onion domes to match the architectural style of Moscow, as the Russian authorities did not tolerate the originality of the churches in the annexed Belarusian lands.

The relationship between the Russian Orthodox Church in Belarus and the Belarusian national identity is complex. Patriarch of Moscow and All Rus’ Kirill, during his first visit to Belarus after his election as the head of the Russian Orthodox Church in September 2009, stated: "Belarus is a homeland for all of us, it is a part of Holy Rus’, historical Rus’," and also that "Holy Rus’ – our historical legacy – is being realized today in various states."

Based on a sociological study on the religiosity of Belarusians, 60% of the population identify as religious. Among this group, 86% identify as Orthodox, 12% as Catholic, and 2% as belonging to other confessions or religions.

Piotr Rudkoŭski, the director of the Belarusian Institute for Strategic Studies (BISS) located in Vilnius, and a political scientist who focuses on the political influence of Belarusian churches, stated in an interview with Media IQ that religion is an important factor in Belarus, but not the determining factor for public political decisions.

According to Rudkoŭski, Belarusians generally have faith in God and consider religion an important aspect of their lives. However, while religion and faith in God dominate Belarusian society, religious institutions and authorities do not have the final say in making socio-political decisions.

Rudkoŭski also notes that supporters of Belarusian independence and national revival exist within all religious denominations. He cites the example of political prisoner Paval Sieviaryniec, an Orthodox believer who is known for his public activism in support of the Belarusian democratic movement.

Moreover, Rudkoŭski observes that the pro-Belarusian and pro-independence trend is particularly strong among Roman Catholics and Greek Catholics. While attitudes towards the Belarusian revival and independence were not always clear in the 90s, there has been a consensus in the Roman Catholic Church for the past 10-15 years in support of independence and the importance of the Belarusian revival. This support was evident in 2020 during the democratic protests in the country.

Information sovereignty lost

Following the contested presidential elections of 2020 and the crackdown on mass protests, the Belarusian regime isolated itself and abandoned its policy of engaging with multiple nations in favor of closer integration with Russia. Pro-government political scientist Aliaksandr Shpakouski observed that "neutrality has been replaced by alliance."

From 1999 to 2020, Belarusian state propaganda initially criticized Russia and accused "Gazprom puppeteers" of meddling in Belarus' internal affairs and supporting alternative candidates in the presidential elections. However, after the election on August 9, 2020, the propaganda aligned with the anti-Western stance of Kremlin propaganda. This synchronization should not be confused with Belarusian propaganda being absorbed or subjugated by Russia. Rather, it indicates a convergence of interests between Minsk and Moscow at a certain stage, as both authoritarian regimes pursue their own goals.

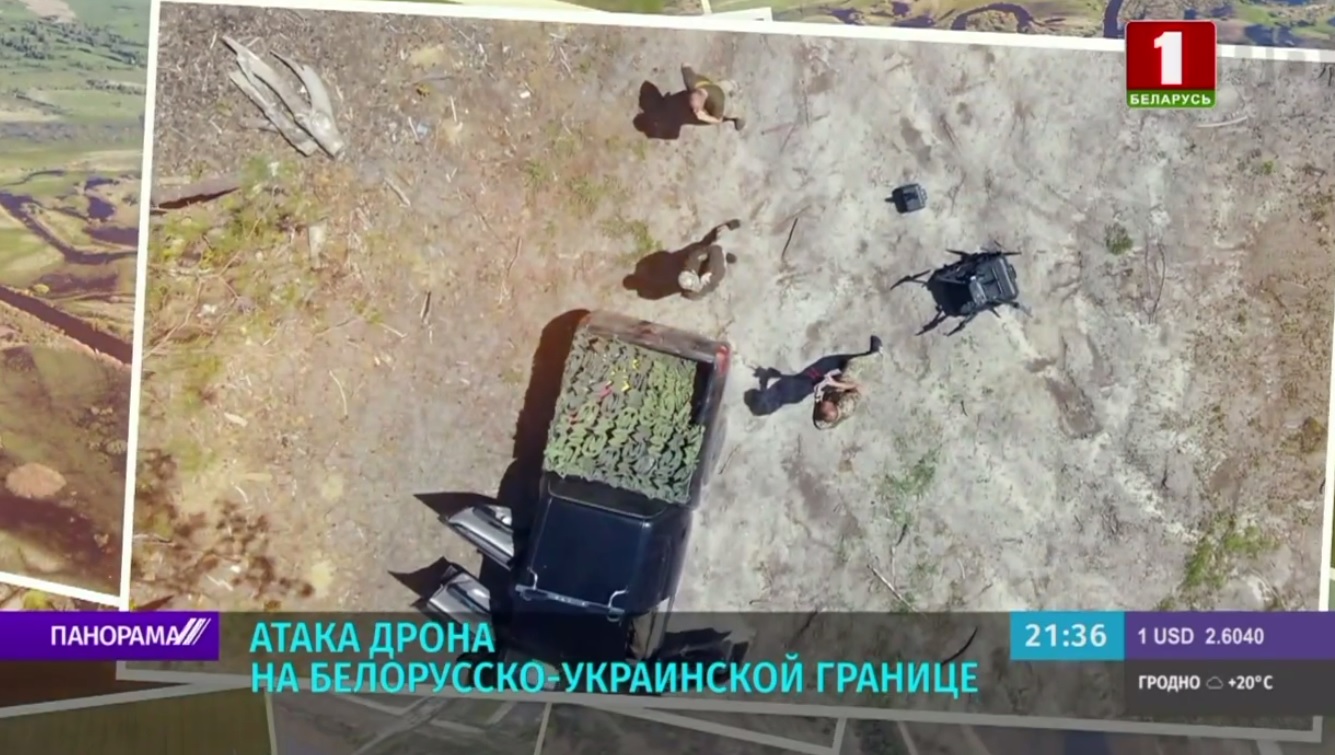

In the fall of 2021 and at the beginning of 2022, that is, on the eve and at the beginning of the full-scale aggression of Russia against Ukraine, official Minsk lost its information sovereignty, one of the components of which was the declaration of non-participation in information disputes of other countries. Belarus abandoned its multi-vector policy in favor of Belarusian-Russian integration, and accordingly, the rhetoric of Belarusian state media has also changed.

Belarusian state media has been broadcasting Kremlin narratives that justify Russia's war against Ukraine, promoting a black-and-white view of the conflict in which everything Russia does is right and everything its opponents do is wrong, even if they do the same thing. Media IQ has reported that this narrative, along with the idea of "Russia and Belarus against everyone," has been advancing since the fall of 2021, contributing to the general militarization of consciousness.

When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, state media coverage was fundamentally different from coverage of the annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbas in 2014. At that time, state media primarily used Russian sources (with occasional reports from Ukrainian state news agency Ukrіnform), but avoided taking any specific stance on the conflict.

Today, Russian state media and Telegram channels remain the main source of information for Belarusian consumers, but Belarusian state channels don’t remove anti-Ukrainian labels (which Russian media use) from its content.

Such approach indicates a clear loss of information sovereignty, which is defined by the principle of information neutrality. This concept means refraining from taking the initiative to interfere in the information sphere of other countries by discrediting or challenging their political, economic, social, and spiritual standards and priorities, as well as causing harm to their information infrastructure and participating in their information confrontation.

Belarusian state media refrained from qualifying Russia's actions as aggression, which is defined as the illegal use of force by one state against another, leading to the seizure of territory, subjugation of the enemy, change in the system of government, or its loss of independence. Instead, they broadcast the Kremlin's position about Ukraine's aggressiveness, claiming that Ukraine attacked the self-proclaimed but Russian-controlled Donetsk and Luhansk People's Republics, as well as the Rostov region of Russia. Russia's actions toward Ukraine are described with emotionally neutral euphemisms like "operation" and "taken under control," and justified by protecting people "from bullying and genocide by the Kyiv regime," "demilitarization and denazification of Ukraine," and the claim that Kyiv is ruled by an illegitimate government or "junta."

Initially, state media cited Lukashenka's statement without reservation that "Ukraine wanted this conflict." Later on, Lukashenka seemed to change his mind when the Ukrainian counter-offensive began. He probably still believes that Russia cannot lose, but he no longer believes that Russia will win. As a result, Belarusian state propaganda is gradually moving away from its reckless support of Russia in the aggression against Ukraine. While they continue to relay the Kremlin's ideological justification for the war, they emphasize Belarus's non-participation in it.

Official Minsk facilitated several rounds of Russian-Ukrainian negotiations, and Lukashenka has repeatedly emphasized that Belarusian soldiers will not set foot on Ukrainian soil. For several months, state media focused on the reception of Ukrainian refugees in Belarus.

The Russian narrative about the “triune Russian people” divided by state borders, which Russian President Vladimir Putin called “the biggest geopolitical catastrophe of the century” back in 2005, has been repeatedly reiterated in subsequent years. Putin has bluntly stated that the Belarusian, Russian, and Ukrainian peoples are “almost the same”, referring to their shared history and “brotherly ties”.

During Belarus' years of sovereign existence, the initially pro-Russian Lukashenka regime has evolved towards understanding the benefits of autonomous development, as reflected in Lukashenka’s formula “Belarusians want to be with Russia today, but live in their own apartment.”

Meanwhile, Belarus remains firmly in Russia's embrace. Official Minsk participates in integration formations such as the Union State, the Eurasian Economic Union, and the Collective Security Treaty Organization for short-term considerations such as access to the Russian market, loans, and preferences in prices for raw materials and energy carriers.

In 2018-2019, Moscow invoked the dormant articles of the Treaty on the Establishment of the Union State, which provide for the creation of supranational bodies and link economic favors to Minsk with deepening integration – in other words, requiring sovereignty concessions.

During this period, the Belarusian authorities lost a dispute with the Kremlin over whether Russia was subsidizing Belarus or fulfilling its obligations on equal economic conditions within the Union State, with debts on loans not being considered subsidies at all. The Lukashenka regime found itself financially dependent on Moscow, allowing Russia to exert ever greater influence.

Conclusion

Assistance in Russia's military aggression against Ukraine increased Belarus' isolation, and it found itself even more tightly embraced by the metropole.

Can Belarus be considered occupied by Russia? Political actors, political scientists, and lawyers, as well as leaders of public opinion, express their views on this topic, but there is no consensus. What are the criteria for this concept? When did this occupation begin? Can every authoritarian regime be considered a form of occupation of its own country? Is the Lukashenka regime completely puppet-like, or does it exercise power on its own territory? The reason for the surge of interest in this topic was the introduction of a draft resolution regarding the acknowledgement of Belarus as an occupied territory to the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine.

Declarations of an "occupied Belarus" allow for a distinction to be made between Belarusians who do not support Russian aggression against Ukraine and the Lukashenka regime, which has clearly lost popularity. This is in itself attractive to critics of the regime. At the same time, the threat of the complete loss of Belarus' state sovereignty is growing.

What can Belarusians do to withstand this confrontation and still break free from the embrace of a neighbor who does not even contemplate that Belarus can be independent of it?

Cover image: Painting depicting the battle of Orsha between joint Belarusian-Lithuanian-Polish forces and Moscow, 8 September 1514. Unknown painter.